THE INCOMPLETE CIRCLE

Speech to Charlotte Thiis-Evensen and Marie Sjøvold at the opening of ‘The End’ at Kunstplass Oslo, 19 May 2022

By John Erik Riley

One of the most frequent clichés about photography is that the camera captures light.

But equally often the photographer captures what we are unable to grasp: the absence of an answer, of a consistent strand in the narrative, of a clear reason for the course of events. That is also the reason we take photographs – not only to describe, but to point to the experience of being unable to capture everything, to illustrate the human experience of seeing clearly and yet fumbling for a meaning.

The camera shows a moment, but time runs on, independently of the picture and the photographer’s own wishes and needs. Before most pictures were distributed on the Internet, each contribution was a death archive, to cite Susan Sontag; it reeked of the past and longing, while photographs today are more often an expression of ‘the now’, of what happened just before they were quickly replaced by new snapshots. In other words the motifs are part of the flow and the immediate sense of time; it’s as if they bathe in a sea of light.

The congenial dinners, the gatherings of friends, the family holidays are so many that it becomes difficult to separate one moment from the other before they are abruptly replaced by new, similar moments created by others with a strong need for expression. The quantity erases the details in every individual case, among other reasons because the individual is omnipresent and eternally broadcasting. The images form part of the same white energy, they are rays of light that increase the brilliance of the accumulation of motifs. In that light we catch sight of most things, and thus we see far less than we think.

In such a situation the photographer – i.e. the photographer who wants something more than just to say “this happened” or “so it was” – must explore experiences that cannot so easily be communicated. The photographs must invite us in, but also disturb us – be disturbingly open in a productive and meaning-seeking way – by communicating a darkness that is difficult to disregard or reduce. In this way the end becomes something other than the end, not just a simple summing-up, but the beginning of something else.

What kind of beginning?

Among other things one where we immerse ourselves in the works – try to find traces of ourselves in them; one where we see them in relation to our own struggles with time, whether small or great. Charlotte Thiis-Evensen’s video work Adrift shows water that flows, raindrops that strike the water surface, and we understand that it is the river of time that we see. Along the way people appear and disappear, faces and bodies drift by like memories and dreams. Thus the video shows us what happens to everything and everyone, how they drift away, disappear for us.

But something else also happens if we pay attention to the screen for a moment. The same scenes repeat themselves, as they often do in video art. On the face of it, it is easy to think that the repetition in this case represents the traditional function of photography, before the camera ended up in our pocket and was linked up with the network: the video shows the river of time, as I said before, but it is the same river we see, again and again. The water and the people are frozen, although they are in motion. The repetition immortalizes them.

In Adrift we are urged to study the passage of time, but the artist also guides us into a state of silent contemplation, because we become aware of someone who sees human beings and the world from above. We are put at an assuring distance from the people who float past, also because the loop in the video is – in the gallery context – eternal. The result is a wondering attitude that could have seemed distanced and cold, but rather has the opposite effect. We feel tenderness for what we see, associate the transitory in the video with our own vulnerability.

Anyone who is within Sjøvold’s and Thiis-Evensen’s The End will notice that the combination of images and video bears the marks of grieving – over more than just the general fact that each moment disappears, each experience is of limited duration.

As everyone who has grieved knows, repetition is a central element of the experience of loss. It is felt of course in everything surrounding the ritualized farewell to the deceased, in which many of the same songs, phrases and gestures recur. For the one who is grieving, the repetition is also a mental and physical experience. The same memories reappear and revolve in the mind. And to the interested visitor one tells the story of the death again and again, repeating the details as if one is still working to grasp that the events have taken place.

Grieving can be described as a series of echoes, while the repetition is an attempt to process the insistent rhythms of the grief, perhaps even to gain power over them. You can’t change what has happened, the echo will always be there – it’s as real as the throbbing of the pulse in the temples for the person grieving – but it’s possible to sing along with it in your own way, to form an individual understanding of it that can make it easier to keep on living. What is art, other than this: sorrow transformed into beauty?

What grief – or what sorrow – has brought Sjøvold and Thiis-Evensen together and made them create The End, we don’t know. The works don’t shout it out; we are given autobiographical glimpses, but they are few. Instead we must ourselves search for the meaning. This slightly obscure, slightly hesitant and searching aspect of the project could have been a weakness, but in The End it becomes a great strength. For The End makes room for us. It invites us in, gives us a breathing-space, and the chance for quiet reflection, such that we see our own experiences in a new light.

Or in a new darkness.

The End is understanding what we have been and who has gone, but also what we leave behind. A Sjøvold photograph taken under water shows a body in motion; at all events it looks as if it is someone who has dived into the water, and in the motif it’s easy to see the connection with Thiis-Evensen’s Adrift. But this time the body is almost invisible to us, covered as it is by layers of white bubbles.

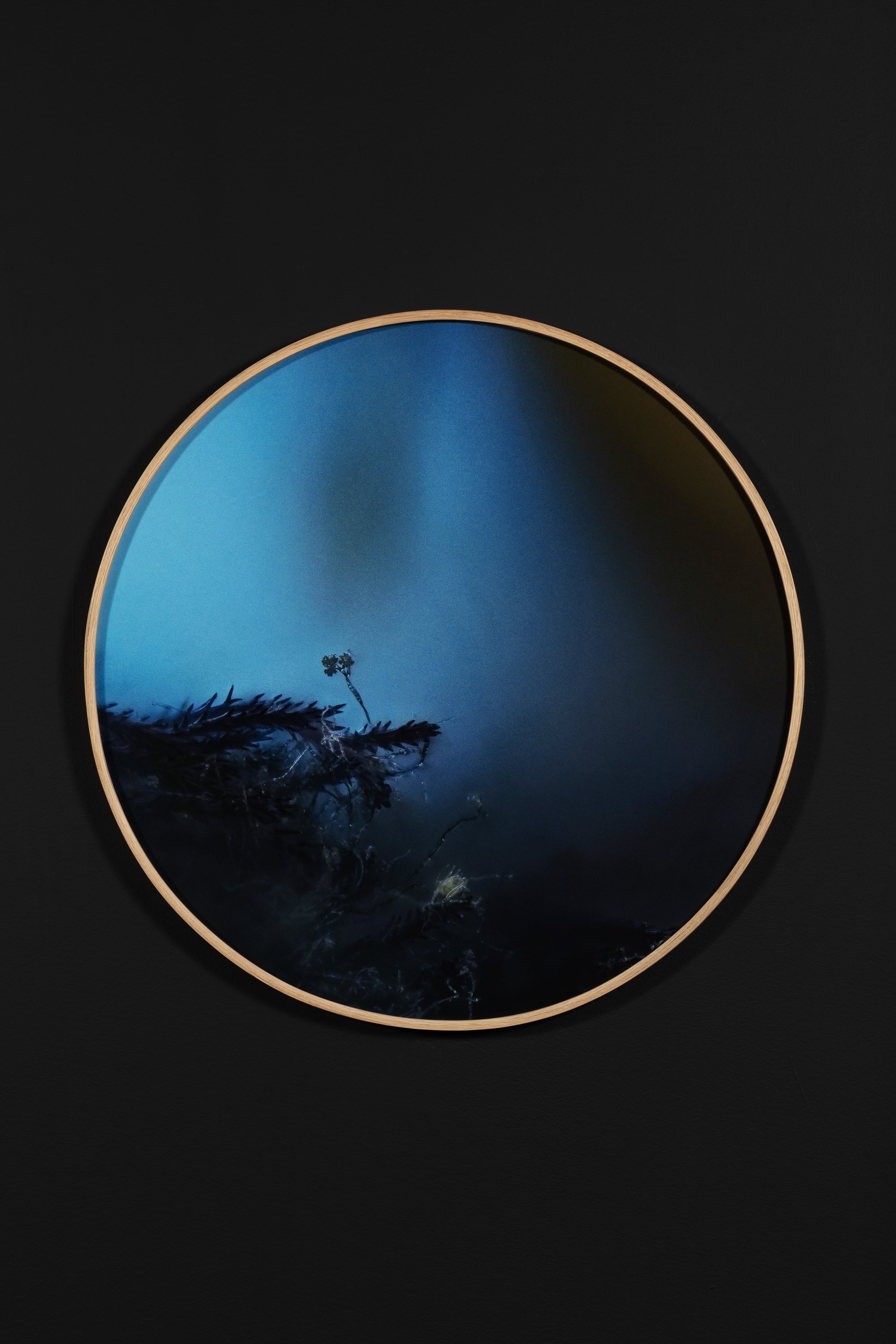

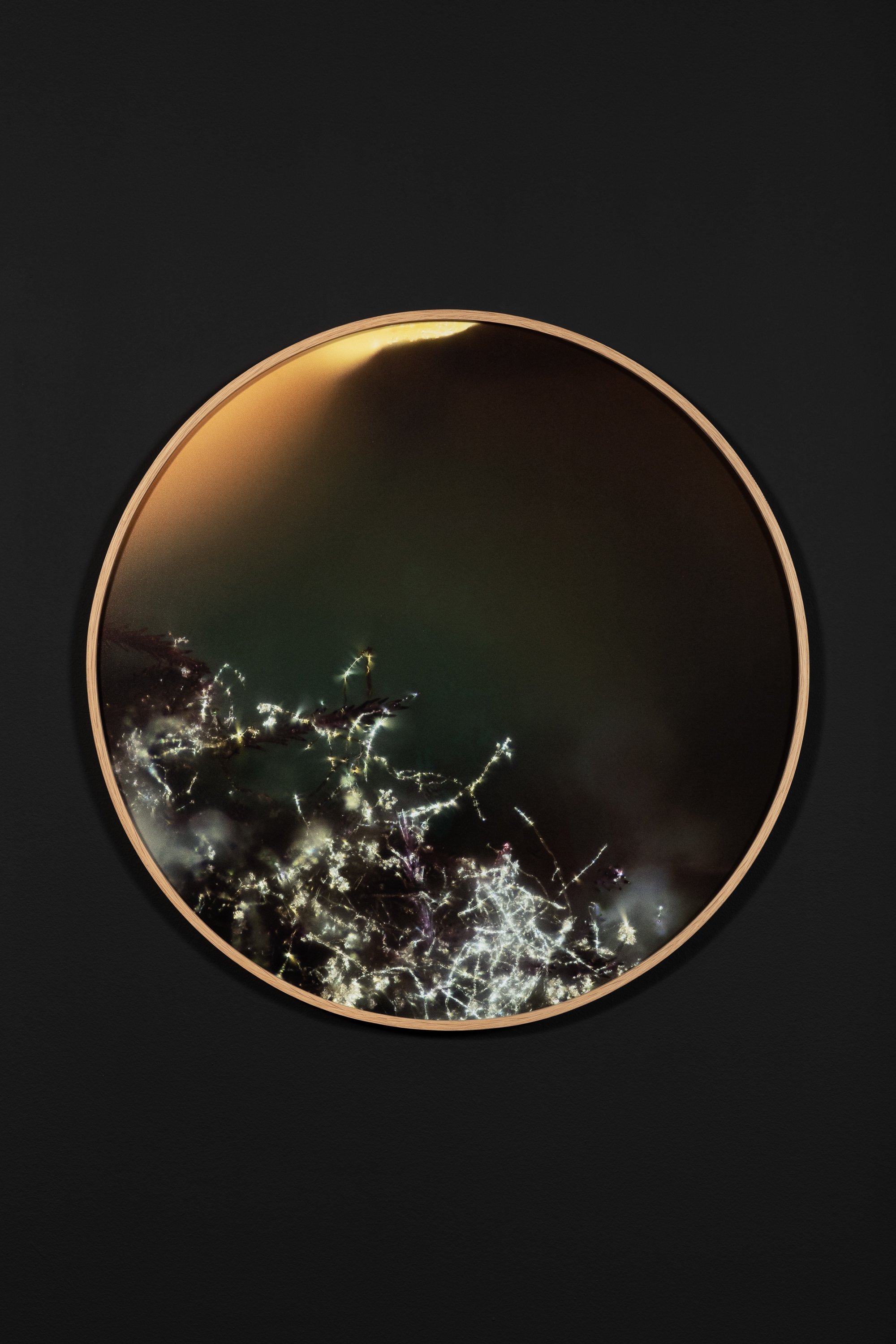

Nor is it easy to know whether the person in the picture is on the way up or down. The bubbles must have been formed by the weight of the body, but the moment when it broke the surface is behind us. The body floats in the picture plane, midway between two states. Only when the gaze turns to the two spheres nearby, circular frames which themselves recall bubbles, do we see the form in the water with new eyes. The pattern in the water is associated with Sjøvold’s close-ups of flowers and plants dying or withering – and the opposite.

The flowers in question have been used in connection with funerals, but have lost their original function. That is, when the photographer takes an interest in them and depicts them with the mixture of obscurity, wonder and intimate closeness characteristic of Sjøvold’s artistry. And it is of course the aftermath we see – when the living plants that we take with us into the church or to the grave also meet their end. Sjøvold’s camera work makes us see this withered hope with new eyes.

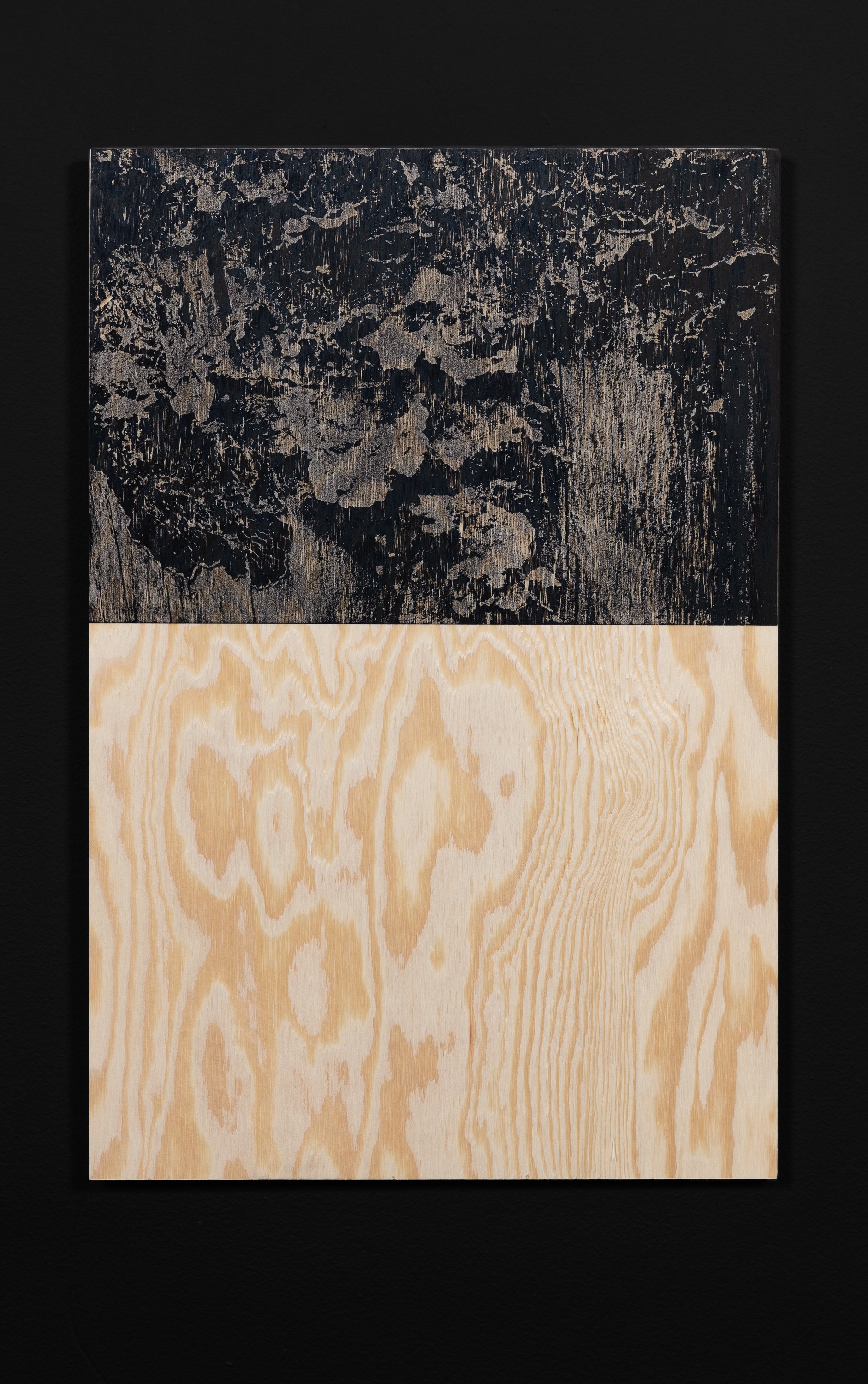

The pictures could have stood as a comment on the absurdity in our rituals, showing how they too are transitory, not to mention desperate, and thus meaningless. The same could have been said about the crumpled photograph; here we see how every attempt at art disappears or is destroyed. And these aspects may be present in the works. But in The End the end is never the end. Here it is impossible to find the point where the circle is completed.

One association leads to the next. The individual elements play on one another in a fruitful way. A bubble in the water makes us think of a framework. And the framework does not demarcate, but rather recalls a porthole, a window.

In the repetitions of The End one finds comfort. One finds life. Energy. That is why I perceive the image of the body under water, enveloped by bubbles, as an ideal rather than an objection. It is an exhortation to find the balancing point, the point midway between gravity and buoyancy, to seek out the experience of being weightless. For creating something, at least something as beautiful and moving as The End, has something of this weightlessness in it. You are drawn down by the grief, surrounded by the darkness, and then you move upwards, towards the light. Or through the gallery door, towards the spring.

Nor does the alternation between the extremes have to be paralysing. I find a liberating mixture of humour and seriousness in a video work which also offers repetitions. We are presented with three screens. In the middle of the triptych there is an elderly woman. Her dancing seems cautious, staged in a friendly way. To the left and right stand two other women, each dancing with her exercise hoop, making characteristic moves associated with sexuality, but also with youth and innocence.

In reality the dance is long since over, everyone following the videos agrees. Nor is it inconceivable that the recording has posed physical challenges, that the women only kept the dance up for a limited period. But on the screen they transcend time and age. The circles surround the women, and the women keep them in motion. They dance for a while, wiggle their bodies, until they lose the rhythm, stop and the exercise hoop falls down.

Another end. Another beginning.